I recently read an article by someone in her 40’s who referred to herself as a “baby crone” (?) and that moved me to write on this powerful archetype. The word, crone, has very unpleasant connotations though its meaning has changed in recent years to indicate an elder wise woman. In its positive modern expression, a woman who has earned the title of crone by the travails of her many years - at least sixty or more of them – has accrued a level of life experience and wisdom that cannot be claimed by those of younger years. That said, in the traditional meaning of the word, a crone is a stooped and weathered elderly woman, thought of as ugly and disagreeable, causing her to be cast as the quintessential witch in old folk tales. She is the cast-out feminine and although that meaning is understandably shunned today - and I appreciate the idea that the crone now indicates an elder wise woman - I also see the crone as the shadow archetype of the tribe or society and I do find it interesting, ironic, and of course, understandable, that modern women would want to reframe the meaning of that word . . . by essentially casting out the crone in her original form.

Let’s look at the word, crone. I find word origins fascinating and essential for a deeper understanding. Etymonline.com states,

“Crone: late 14c., "a feeble and withered old woman," in Middle English a strong term of abuse, from Anglo-French carogne "carrion, carcass; an old ewe," also a term of abuse, from Old North French carogne, Old French charogne, term of abuse for a cantankerous or withered woman, also "old sheep," literally "carrion," from Vulgar Latin *caronia (see carrion). Perhaps the "old ewe" sense is older than the "old woman" one in French, but the former is attested in English only from 16c. Since mid-20c. the word has been somewhat reclaimed in feminism and neo-paganism as a symbol of mature female wisdom and power.”

As well, etymologyworld.com states:

“Crone: The word "crone" comes from the Middle English word "crones," which in turn derives from the Old English word "crone," meaning "old woman." The ultimate origin of the word is unknown, but it is thought to be related to the Sanskrit word "krun" ("hunch"), possibly referring to the way elderly women are often depicted as being bent or stooped.”

Webster’s 1828 dictionary defines “crone” as “An old woman” and the modern Mirriam-Webster dictionary takes it further, defining the word as, “a cruel or ugly old woman.”

Obviously, “crone” is hardly complimentary, rather it has been used as an insult directed toward certain elderly women who were no longer viewed as desirable or relevant by the community, and often demonized. Tragically, certain elder women have paid dearly for this representation over the centuries and even today, many elderly women feel invisible and undervalued. However, looking more deeply into the crone archetype as a metaphor for nature herself, we see a force that represents nature’s refusal to remain static, however much we desire to keep that vibrant, fertile and pleasing expression as just that. Nature shows us with the passing of the seasons that there is a time for decay and withering and ultimately death and it is not always pretty. At the end of the day, it reminds us of our mortality and the inevitable decline in people (if they make it that far) that can also bring with it cantankerousness, bitterness, pain, disease, dementia and even madness.

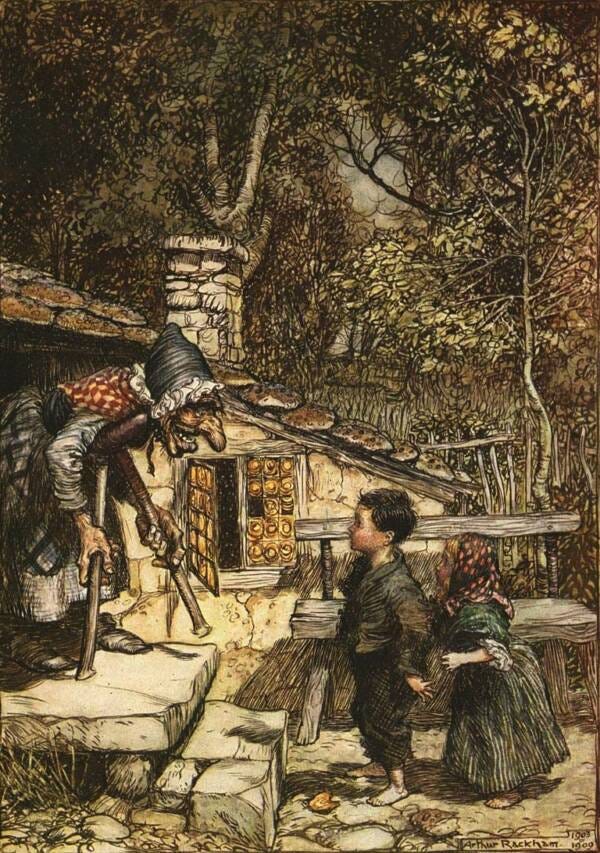

Folklore is rife with stories of scary old women who threaten children and adults alike with harm, and unleash curses and black magic spells on the hapless. Ultimately, they represent the darkness that threatens the light of life. A well-known example is the witch in Hansel and Gretel who lures children to her home in order to devour them. As well, we have the wicked stepmother in Snow White, who is venomously jealous of Snow White’s youthful beauty and seeks to destroy her with a poison apple.

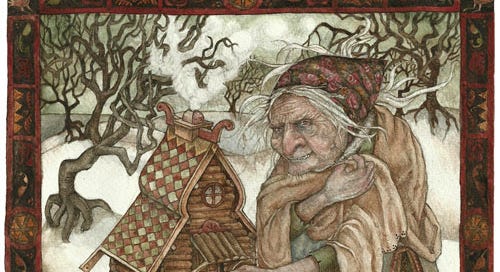

The crone, Baba Yaga, is the most recognized character in old Russian folktales. Baba means “grandmother” and yaga means “witch.” She rules the forest, a place of darkness and probable danger, where she serves to initiate those who enter as either evil witch or kindly grandmother. Those who break her rules and show disrespect face dire consequences. She, herself does not die and so serves as the perilous threshold guardian to the next level of experience. No matter how far up the ladder of life we climb, there is always a destructive or testing force to be met and dealt with and in folktales of old that force was often a crone, usually portrayed as a witch skilled in the dark arts with a powerful lesson to teach.

That ominous power was thought by superstitious communities of old to be associated with certain elder women rumored to be practitioners of the dark arts. This concept was exploited by the Church and had a tragic and horrifying effect during the 2.5 centuries of public burnings in Europe during the witch mania of the Middle Ages where thousands of people, men and women alike though primarily elder women, were tortured mercilessly and burned alive at the stake. From Ford’s Witch of Edmonton, we read:

Countrymen: Hang her! beat her! kill her!

Justice: How now? Forbear this violence!

Mother Sawyer: A crew of villains. A knot of bloody hangmen set to torment me! I know not why!

Justice: Alas neighbor Banks! are you a ringleader in mischief? Fie! to abuse an aged woman!

Banks: Woman! A she hell-cat, a witch! To prove her one, we no sooner set fire on the thatch of her house, but in she came running, as if the devil had sent her in a barrel of gunpowder!

The collective imprinting from that terrible time continues to impress itself on the deep psyche of the masses and many modern stories, such as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, feature the villain as a crone possessing immense dark powers and a thirst for control at all costs. And of course, a popular Halloween costume is that of an old witch.

If I had to sum up the historical definitions of the word, “crone” in one word it would be fear. The crone is quite elderly, having lost her youth and the vitality of her middle years and in many a village of old there were the ones who roamed in a state of madness or dementia, inspiring misunderstanding and preposterous rumors. The crone represents the final chapter of life and the inevitability of death, the profound mystery of which has been cast out entirely in modern culture. Youth is celebrated today and my late teacher, Dr. Brugh Joy, MD, used to say that we are a nation of children, infantilized and bereft of the essential initiations traditional people gave their young to lift them from childhood into adulthood.

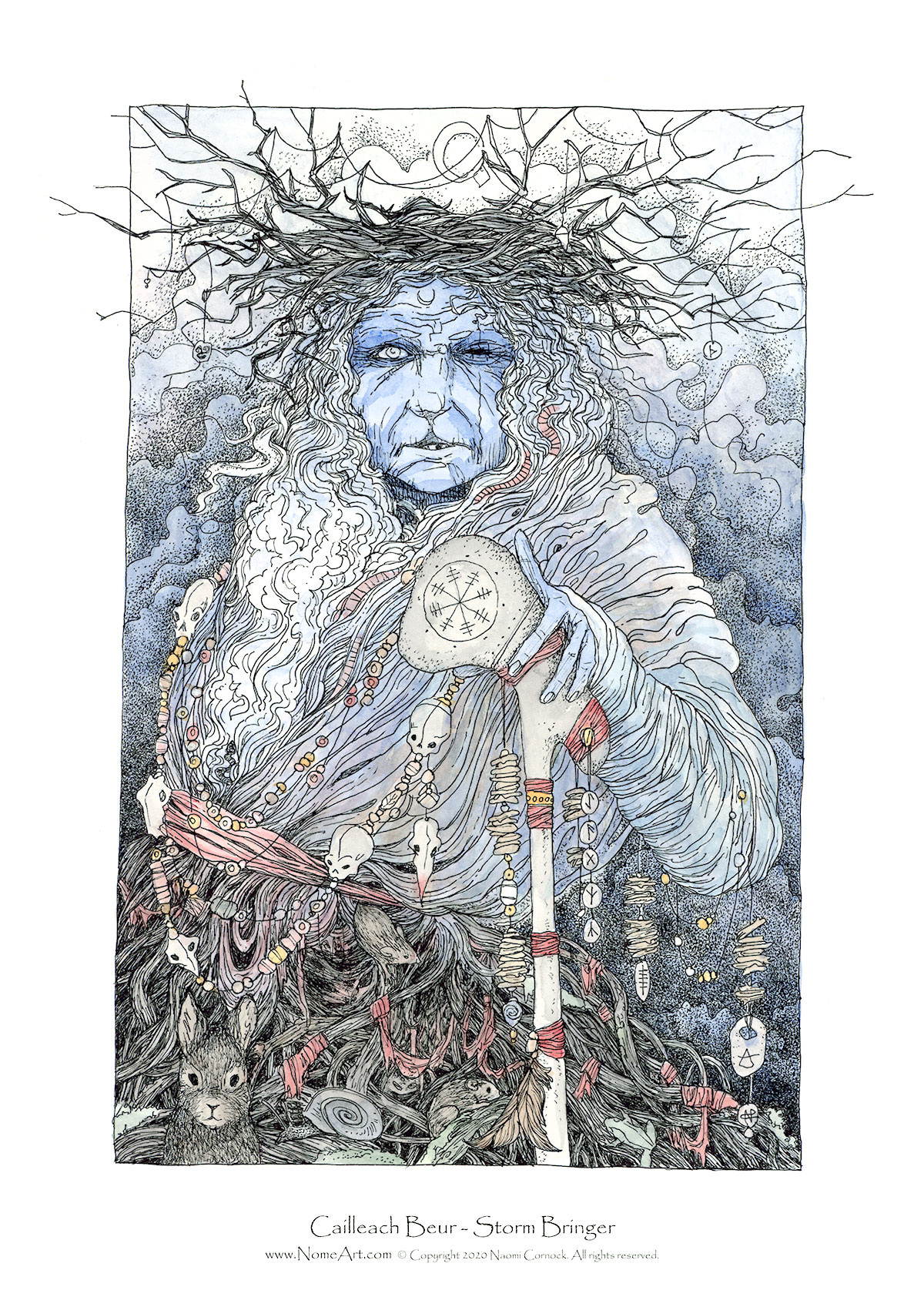

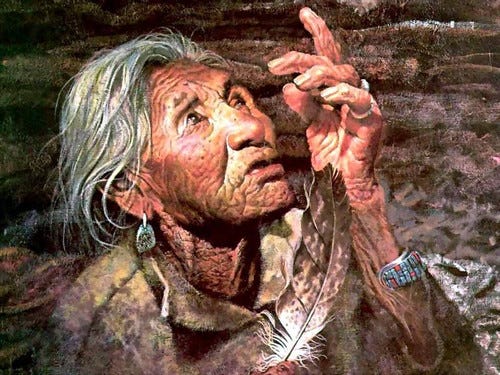

In traditional cultures of old, the elders were regarded as the teachers and holders of wisdom and their advice was actively sought out. In fact, for these cultures the dark expression of the crone archetype was accepted and feared and also respected, as she often represented the untamed and perilous side of nature in her many expressions. For example, the ancient Cailleach of Gaelic myth was the hag who represents the harsh and barren time of winter with its great storms. In spring she is reborn as Brighid, and the earth blooms again. This is a clear illustration of the triplicity of Maiden, Mother, Crone, which is a timeless theme that ultimately speaks to the cycles of life.

That said, most people today still associate the word, crone, with an ugly old woman, which again was its original meaning. It is no surprise that most modern elder women have zero interest in using that word to describe themselves, including my 86-year-old mother. I am excluding of course, the neo-pagan, feminist and new age folks who have reframed the word to indicate an elder woman of wisdom. Author and Jungian analyst, Jean Shinoda Bolen, MD, played a major role in this reframing through her book, Goddesses in Older Women. I do think though, that the harsh, original definition of crone deserves to have its place and certainly when we think of the triplicity of maiden, mother, crone with regard to the cycles of nature, the crone represents the decaying forces that are none too pleasant compared to the beauty of spring and the promise it brings.

The undiluted folklore of old has not been shy with regard to its presentation of what we would think of as evil forces that punish both the innocent and the unwise. In addition to a variety of underworld beings, monsters and the like, the human embodiment of that evil is presented primarily as the crone and also the elder male, both of whom are usually portrayed as wizard/witch/shaman with supernatural powers. In Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales, Marie-Louise von Franz writes that this dark force is not a religious one of good and evil but rather “it belongs to the realm of purely natural phenomena. . . It is for this reason that fairy tales are so important. We find in them rules of behavior on how to cope with these things. Very often it is not a sharp ethical issue but a question of finding a way of natural wisdom. This does not mean that these powers are not sometimes exceedingly dangerous.”

Interestingly, von Franz then goes on to describe a story featuring Baba Yaga and Vasilisa the Beautiful. Of the crone/witch Baba Yaga, von Franz writes: “In the Russian version one can see clearly that the Baba Yaga is the great Mother Nature. She could not talk about “my day, my night” if she were not the owner of the day, of the night, and of the sun, so she must be a great Goddess, and you could call her the Great Goddess of Nature. Obviously, with all those skulls around her hut, she is also the Goddess of Death, which is an aspect of nature. (One is reminded, for instance, of the Germanic goddess of the underworld, Hel, from which our word hell comes. She lies in a subterranean hall where the walls are built of worms and human bones.) So, she is a goddess of day and night, of life and death, and the great principle of nature. Also, she is a witch, which is why she has a broom, like our witches who ride on broomsticks. She goes around in a mortar with a pestle, which makes her resemble a great pagan corn goddess such as Demeter in Greece, who is the goddess of corn and also of the mystery of death. The dead in Greek antiquity were called demetreioi, those who had fallen into the possession of Demeter, like the corn falling into the earth. Death and resurrection of the wheat was supposed to be a simile for what happens to man after death, so those skull hands which took the corn and poppy seeds had to do with the mystery of death.”

The natural inclination of many people is to cast out this perceived unpleasant yet altogether natural and essential expression of nature and humanity. Yet the crone in her original form does not comply with one’s preferences, whether one is well-meaning or in resistance. In this expression she is free from the collective standards of beauty and social decorum and as well, predictability. She is closer to death than most and that has given her a unique perspective we would be well served to learn.

Now of course, we have the kindly crones of folklore, who are the grandmother keepers of otherworldly knowledge and wisdom used to serve and advise many a story’s hero and heroine. In the Gaelic myths the crone or hag was often a faerie woman who appeared as a crone to test the heart of the hero. In Niall of the Nine Hostages, the five sons of Eochy, the high king of Ireland, venture out on a hunt. They kill a stag and one of the sons, Fiachra, is sent to fetch water. Standing by the well and serving as guard is a withered old woman who tells him he can only draw water if he lies with her. Though Fiachra kisses her his disgust is obvious and she sends him away. The other three brothers attempt to fetch water yet they cannot conceal their revulsion when given her requirements for access. Niall then appears and agrees to sleep with her, after which she reveals herself as a beautiful young woman who rewards him for his kindness by offering not only the water but also kingship over Ireland for many generations.

Another kindly crone is La Befana, the Christmas witch of Italy, who flies through the sky on her broomstick, her bells jingling on the eve of Epiphany to gift candles, sweets and other presents to the children on Epiphany day, January 6th, which is 12 days after Christmas. Her name, La Befana, originates from the Greek word, “Epiphaneia,” which is the religious festival of Epiphany. For the ancient Greeks, an epiphany was a manifestation of the god or goddess experienced by a mortal who then received protection and an abundance of gifts.

A Christian legend has it that La Befana was visited by the three wise men seeking the way to the infant Jesus. She did not know the route but welcomed them to stay the night. The next day they invited her to join their journey but she declined, having too much work to do as a housekeeper. She later regretted her decision and packed a bag of gifts for baby Jesus whom she searched for in vain and to this day she continues to seek him out, leaving gifts for children along the way. La Befana is portrayed with disheveled hair, wearing a patchwork skirt and an old shawl. She is kindly and she rewards good children, while punishing misbehaved children not with the wrath of the dark witches but simply with gifts of onions, garlic and coal.

There are many more examples of kindly wise crones in folklore throughout the world and of course, the archetype of grandmother is one of wisdom, nurturing and kindness. For as maligned as the archetype of the crone has been she is ultimately the holder of life experience, mundane and occult knowledge, and profound wisdom. In both her guises as malevolent and benevolent crone she demands respect and teaches the hard lessons with their repercussions as well as their rewards. She is no baby and in both her expressions she deserves our respect and honoring.

Sad what happens when our wisdom elders are feared instead of revered. Can only remember once, we were invited to a ceremony for a year old baby by some young folk who follow the work of Martin Prechtel, a Guatemalan shaman, and Krys was treated with that respect by them. It was almost a shock, given our cultural veneration of vapid youth. Thanks Shonagh for another wonderful and beautifully-researched piece!